This story was originally published on January 21, 1987, under the title “Oyster Light.” It is being resurfaced as part of the Weekly Classics series.

Our corner of the world—particularly in the winter—is so lightless that it seems almost an outdoor cave. Underfoot is rock, covered with a this layer of moss and a mulch made up primarily of damp, rotting pine needles. Overhead is a dull, gray, lifeless dome, oozing moisture. Northwesterners are perched in between, clinging desperately to manmade light and warmth, looking upward without expectation. Winter nights are black and wet, winter days emit a tentative, sourceless glow, only eight hours in duration, that comes on slowly overhead, never quite seems to reach its fullness, then steadily darkens. These days are like shallow inhalations and exhalations of light, taken by an invalid.

The weakness of our daylight, according to Bruce Renneke, Seattle’s lead National Weather Service forecaster, is owing to both cloud cover and latitude. Our sunniest month—July—averages just ten clear days; over the course of an entire year, the Northwest averages only 55 days without cloud cover. From October through March, it is almost constantly cloudy, there being only 17 clear days during those six months, 27 days that are classified as partly cloudy, and 137 completely cloudy. December is the darkest month, with only two clear days; March—normally associated with spring and relative lightness—averages only three.

The cloud-caused lightlessness is compounded by the Northwest’s latitude, which combines with the winter tilt of the earth to thicken the atmospheric filter the sunlight has to penetrate. Our sun during the day appears to be trying to skulk unnoticed around the horizon. “With that kind of sun angle,” Renneke says, “it really doesn’t matter if it’s cloudy—the light is dimmed by the lattitude factor.

Unlike most northerners, we are denied the winter consolations normally provided by nature. To the east, from the Cascades on, nature compensates for the cold and shortness of the winter days with clear skies, dry air, an absence of light-absorbing foliage, and a blanket of reflecting white snow. Winter days, for many northern people, are the brightest, clearest days of the year. Here, the obscuring clouds overhead are abetted by spongy air and a dark green landscape. These factors are to earth-bound light what a black hole is to celestial matter.

Thomas Hardy caught such thin light memorably in the opening passage of Return of the Native, describing Egdon Heath. “The face of the heath,” he wrote, “by its mere complexion added half an hour to evening; it could in like manner retard the dawn, sadden noon, anticipate the frowning of storms scarcely generated and intensify the opacity of a moonless midnight to a cause of shaking and dread.” So too out evergreen-darkened landscape absorbs light until the dim light in the sky seems to be directed upward from somewhere behind the horizon rather than earthward from above.

This is something curiously inspiring about out winter light. Direct, unmediated sunlight is harsh and compromising; Northwest light, like the fabled Northwest temperament, is soft and laid-back. It is directionless, lush, luxurious, and romantic. It is amorphous-not so much beamed from a single source as aglow all around us. It so softens shadows that there is virtually no contrast between light and shade. We move through a dreamily dim, carefully ill-defined world of rounded edges and comfortable contours. Our light, like candlelight, looks kindly on flaws and brings the ordinary lavishly alive. On the grayest of days, it imparts to grass and moss an eerie, unearthly luminescence. It can be more alluring to the eye than a sunswept South Sea beach, clanging with vicious whites and knife-edge shadows.

The sunlight itself, by the time it penetrates the Northwest’s atmosphere, is green. According to UW atmospheric physicist Dr. Kenneth Clark, unfiltered sunlight’s color “is a smooth spread from the shortest violet color, getting lighter and lighter up through the greens, into the red-infrared end of the spectrum. Most of the sun’s energy goes into the yellow-green section.” Having passed through successive layers of upper atmosphere, cloud cover, and low-level aerosols, the sunlight’s spectrum, Clark says, “is full of gaps and notches by the time it hits the ground. Many of its wavelengths and colors have been absorbed, and molecules in the air scatter the light, particularly at the blue-to-ultraviolet end of the spectrum.” Since the Northwest abounds in clouds and aerosols—the latter defined by Clark as “concentrations of tiny particles of moisture, soot, ice crystals, sulfates, and so forth”—the light we see is considerably weakened and scattered.

Absorption is less responsible for the dimness of Northwest light than the scattering effect of moisture. “When sunlight hits the top of clouds,” Clark observes, “all the colors bounce off. Light entering the top of a cloud just gets lost going sideways. Part of it gets scattered horizontally, and it just loses itself that way.” The same effect, on a subtler scale, obtains when there is abundant moisture in the air. “Light bounces off little particles of water, with the net result that it gets weaker and weaker as it comes down.” Not only does it get weaker, but it casts and reflects horizontally, washing out deep shadows and spreading a wondrously diffuse, subtle, gray glow to the air all around us. It is an isotropic light-light traveling in all directions at once.

Clark believes that a similar effect is at least partly responsible for the glow given off by some vegetation on overcast days. “Grass isn’t luminous in terms of generating light,” he says, “but it does a better job of reflecting. Dark greens don’t give you much scattered light, but lighter, yellowish greens do. And I would think that the little beads of water on blades of grass—surface tension draws water into beads—act as better reflectors and scatterers of light than flat green surfaces do.”

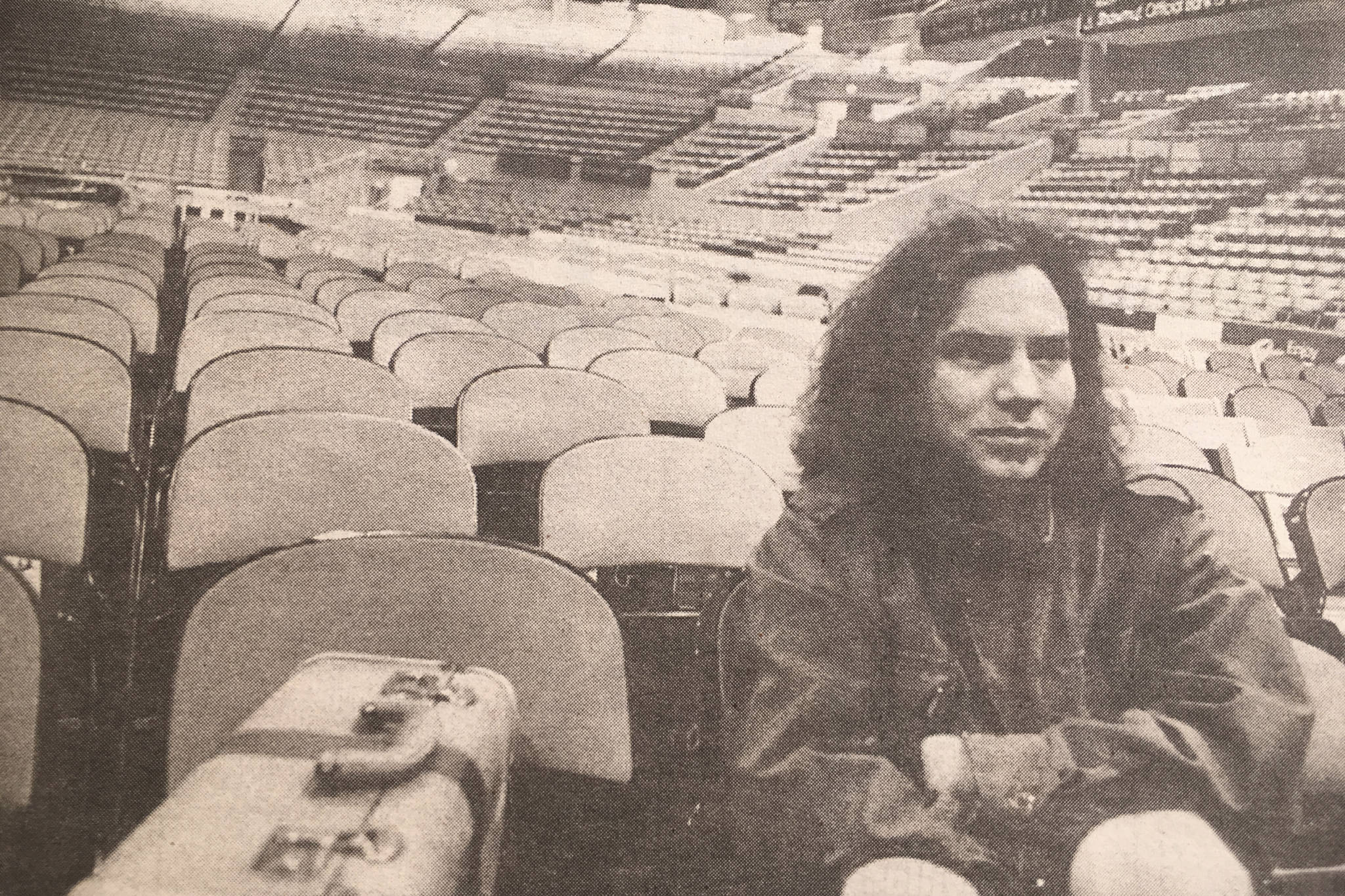

Something comfortable or fascinating about Northwest winter light has inspired a certain subconscious devotion to dimness. We pay lip-service to the sun, yet we appear to prefer murk to sunlight. While residents of cities whose climates are far less temperate than Seattle’s—Chicago, Denver, Kansas City, Green Bay, New York, Cleveland, to name a few—brave the elements to watch professional footbal and baseball games outdoors, Seattleites do the opposite, creeping into a chilly, comfortless edifice that presents an overhead expanse of midwinter gray in the middle of a sunny summer day. Watching 54,000 fans streaming into the Kingdome for a Seahawk exhibition game on a bright August afternoon is like watching a mob of beetles frantically crawling under a rock to get out of the sun.

We also revere those who accent Northwest murkiness rather than those who help us escape it. Our best-known, most established visual artists—Morris Graves, Mark Tobey, Kenneth Callahan—made their living off the Northwest’s regional myths of rainy skies and gray days. Even D.B. Cooper is an embodiment of Northwest dimness. His eyes obscured by sunglasses, he stepped briefly into the faint Northwest limelight one November day, then melted away into a rainy winter sky, never to be seen again. Cooper’s sunglasses are the classic emblem of the Northwesterner’s ambivalence toward the sun. For all our winter lamentations on the lack of light, let the sun finally come blazing brightly through in spring and we immediately try to Obscure it. “From what I understand,” says Western Optical’s Joannie Zelasco, “we are the sunglass capital of the world.”

Springtime, associated elsewhere with rebirth, renewed energy, and eternal hope, is greeted in Seattle by a surge in the number of suicide-related calls to the city’s crisis clinic. National suicide statistics refute the commonly held belief that Seattle weather is responsible for an abnormally high Northwest suicide rate. Cloud-bedimmed King County ranks only 12th in the nation in suicides per 100,000 people, far behind such sun-drenched locales as California, Nevada, and Florida, which rank first, second, and sixth, respectively.

This is not to say that people here don’t get depressed by the lack of light in winter. Since 1979, Harborview psychiatrist Dr. David Avery has been studying a malady he calls Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD), or winter depression. “It’s a widely recognized syndrome,” he says. “People who feel fine in spring and summer experience a profound change in winter. They may sleep 10, 12, 14 hours a day, their food intake increases, they gain weight and crave carbohydrates. They suffer from low energy, withdraw socially, and have trouble going to work. It can progress to the point of hospitalization. And people report relief of their symptoms if they travel to southern latitudes.”

Psychiatrists believe that the blahs are triggered by the lack of light rather than the lack of warmth in winter, and Avery is testing this theory with bright-light treatment of his patients. Using full-spectrum lights that are five times as bright as normal office light, Avery exposes his patients to it for varying periods, at different times of’ the day. He is convinced that the light therapy is effective.

As far as the exact nature of the disorder is concerned, there are currently two hypotheses floating around. “One,” says Avery, “involves the shorter length of the photoperiod in winter. The body senses the shorter period, and adjusts accordingly. The other is the photon-counting hypothesis, which states that the total amount and degree of white light is sensed by the body and it responds to a decrease in the total amount over a 24-hour period.” Avery believes that the first hypothesis is correct. “It’s clear that the circadian rhythm in the body can be manipulated by changing light. You can change. the body clock of an individual by giving him two hours of bright light. It appears as though the optic nerve makes connections with the hypothalamus, and within the hypothalamus there’s a circadian-rhythm modulator that regulates sleep and body-temperature cycles.”

The most specific measurable organic effect of bright-light therapy is its ability to alter the pineal gland’s production of the hormone melatonin. (Not to be confused with melanin, which affects pigmentation, melatonin is a brain chemical known to induce sleep and affect the reproductive cycles of animals.) “There is a self-regulating rhythm to melatonin production,” Avery says. “Bright light inhibits its production.” But in dim-light settings like a Seattle winter day, there is so little light that the pineal gland produces melatonin as if it were in 24-hour darkness.

For all he has learned about light and depression, Avery is still groping in the dark when it comes to determining exactly how the human brain and natural light interact. “It’s a gross understatement to say that the brain is complex,” he says. “There is almost an infinite number of possibilities as to why people have winter depression. These hypotheses about light are the ones that have the most data-support.”

Avery is convinced that Seattle’s dimness, temperate winters, and number of winter-depression patients demonstrate that there is a definite link between light-deprivation and depression. “Seattle is an ideal place to study it, both because of the latitude and because our winters are mild enough to rule out temperature as a factor,” he says. He was also impressed by the number of Seattleites who called him about winter depression when word of his work first hit the press seven years ago. “It, is clearly present in significant numbers in Seattle. And it seems like it varies considerably within the city. Some people have even moved away because of it.”

Although his work tends to confirm the widespread belief that Seattle is depressingly dim, Avery is the first to caution that he treats clinically depressed patients, and that their maladies tell researchers little about the population as a whole. There has been at least one recent study of the general population indicating that Seattle’s winter light has gotten a bad rap. Psychologist Judith Heerwagen, of the UW’s Center for Planning and Design, conducted a pilot study of 22 Seattleites’ lighting preferences season to season. “I did the study,” she says, “because it has been suggested that the Northwest has a high level of seasonal mood changes.”

Heerwagen divided her subjects into two groups—“Those who claimed to have seasonal mood changes and those who claimed to feel no change. Those who claimed to feel depressed in winter indicated that they withdrew, became less active, gained weight, and generally had less energy during those months.” Working with 11 people in each group, Heerwagen had her subjects enter a room at various times throughout the year and set the light at whatever level they wanted. The room had three types of light, each controlled by dimming switches. One—wall-wash fluorescent lighting—was indirect; one was a task lamp over a desk, and the third was a simulated window with light coming through it. “Consistently,” Heerwagen says, “those who claimed their moods fluctuated with the seasons wanted much brighter light than the others. And they would crank the window-light up, higher than the other two light sources.”

There were two other important aspects to her study, however, that kept Heerwagen from attributing too strong a connection between light levels and moodiness. “During the study, we gave our subjects series of questionnaires on their mood, and the results showed no changes in mood from season to season in the group who claimed to feel depressed in winter. These people may have been suffering from depression in winter, but that depression didn’t go away in June. It was just that those who reported winter depression were generally moodier people—their moods fluctuated more all year around, and they would attribute their depression to winter.”

Heerwagen also observes that when she selected her subjects, she tried to get two groups who were evenly matched in every possible variable. “We gathered information on ethnicity, age, and so on,” she says, “so that the groups were matched as closely as possible. The only thing we couldn’t match was the length of time they had spent in the Northwest. And it was clear from the data that this is a big factor in attitudes toward winter. People who had the most changeable moods were those who had been here the shortest period of time. And those who said they didn’t undergo seasonal mood changes had been here the longest. There seems to be a definite adaptation point—people who had been here ten years or less seem to have been the most affected.”

Seattle is unquestionably immigrant-heavy, and the problem of winter dimness may be a matter more of adaptation to the Northwest than of some fundamental human craving for light. According to Jean Moehring of Seattle’s Department of Community Development, 52 percent of Washington’s residents were born outside the state, and 10 percent of those living in the Seattle metropolitan area lived outside Washington five years earlier. The high percentage of people who come from brighter, drier climates has undoubtedly made Northwestemers in general more weather-conscious. “I think people tend to think they’re more depressed in the winter than they really are,” says Heerwagen. “Seattle is just weather-crazy. We’re always talking about the weather in this city. When it’s nice and sunny here, it’s a big event—newscasters always comment on it. So there may not be as much depression in the winter here as we think there is.”

If there’s less winter depression in Seattle than there seems to be, it undoubtedly is owing to the quality rather than the quantity of its natural light. It is surprisingly easy to find people who rhapsodize about Northwest light as emphatically as others complain about it. Even more surprising is the correlation between a person’s dependence upon natural light in his or her work and that person’s esteem for Northwest sunlight: Those who work most with light not only profess the greatest love for the Northwest’s, but derive a good deal of their inspiration from it as well. “The thing that always impresses me here is all the intermittent shafts of light, the brilliant little zings of sunlight that come through everything,” says architect Mick Davidson. “I guess the liveliness of the light is probably it—I really notice that a lot. It’s really dancing around up here. And when you take a look at natural objects in the sun, you see more dynamic reflectance than you see in the South or the Southwest. It’ll be dancing off little leaves, and it’s so diffused and soft that you get all these backlit effects. It’s not bouncing off a harsh rock or something. We don’t have anything like the harshness of, say, February sunlight in Vermont, where you have everything white on a real clear day. That’s almost too much to take.”

As Davidson sees it, the Northwest is characterized less by a lack of light than by a richness and life in the light that is unequaled anywhere else. “In other parts of the country,” he says, “light is pretty much cut-and-dried. Here, it’s almost an enigma. It just seems to be evanescent. It’s not constant—that’s the real richness.”

Northwest light changes and moves and dances, Davidson says, because its source, during the course of a day, changes angles almost constantly. Because the Northwest is so far north of the equator, the path from sunrise to sunset traces a circuitous course along the horizon rather than directly across the sky. The sun moves around a house rather than over it. “It’s just amazing where the sun rises and sets here,” Davidson Says. “In terms of where the sun hits a house and how it moves around it, we’re so much richer than in a place like LA or Florida, where there just isn’t that much variation. It’s just there, overhead, where here it’s always going around.”

Light penetrates deeper into Northwest homes because the sun is generally too low in the sky to be hidden by a home’s eaves. The low sunlight angle, combined with the round-about trajectory of its source, makes natural light a more integral part of the indoor environment than it is elsewhere in the country. “The fact that the sun can penetrate a lot more into houses here means you get a different quality of light,” says Davidson. “You get more reflectance off manmade stuff, and you don’t have the glare you have other places because the light is so soft. You get a different sense of daylight here because it can penetrate so far indoors.”

Where in warmer, brighter climes, the low sun angle would be a detriment—design in those areas being devoted in large part to keeping light out of a house—in the Northwest it is an architect’s dream. “You welcome the light here. Natural light also has an element of heat to it, and both the light and the heat are welcome. In other climates, you try to avoid that—here, you open it up. And because the light changes so much, it is the one really dynamic factor you can work with in design.” Davidson incorporates skylights and as much window surface as energy codes will allow in order to get lots of light into his houses. “The light isn’t all that strong here, so I try to bounce it off walls, which diffuses it and gives a soft illumination to rooms. And I look to see how many places I have that would be good places to sit and read a book in natural sunlight. It’s kind of an informal test of my designs. If I can follow the sun around the house so there’d be a good morning room, a noon room, an evening room—a good spot in each room to sit and read a book—then I feel I’ve used the light well.”

In Davidson’s view, it is not so much that the architect here has more to work with as that the Northwest environment calls for a different kind of creativity. He sees the Northwest as almost a direct opposite of Italy where contrasts between between sunlight and shadow are remarkably sharp. Interplay between light and shade there is so integral to design that the Italians, during the Renaissance, introduced into architecture the notion of “negative space”—the shadows and holes in a structure that would combine with the sunlit surfaces, or “positive space,” to bring a pulsating rhythm to a building and its surroundings. “There,” Davidson says, “you design all the time for light and shade. Michelangelo in all his architectural renderings was manipulating the surfaces, the facades on his buildings. That technique made sense because the light was there to play off of constantly. Most of the time, the sun was out shining. Here, it’s different. Because the light isn’t such a dominant, searing force, we’re much more open. We have much more glass. We don’t have so many portals or so much framing of views.”

To photographer/filmmaker Bob Peterson, Northwest light naturally provides conditions photographers elsewhere in the country work hard at creating artificially. “It’s something we take for granted up here,” he says. “Other people come up and they’re amazed. Hard light highlights flaws, and photographers are always looking for ways to soften it. By bouncing strobe lights off umbrellas, you can soften light. Or you might put a strobe inside a 6- to 8-foot light-box, a ‘soft-box.’ Here, when it becomes overcast, it’s like the sun is a giant soft-box. The light is so soft, it’s like this box you’d pay $2,000 to $3,000 for.”

Peterson has worked all over the world and finds that he spends much less time here looking for workable light. “I remember when I first moved away from here years ago, and I was sent down to Atlanta to shoot a football game. There was just bright pure sun on the field—I couldn’t believe it. I prefer it here. It was so light there, the sun was directly over my shoulder, and I couldn’t get the soft, backlit effect I can get here anytime.

The light here is easy for photographers and filmmakers to work with both because of the filtering moisture in the air and because of the low angle of the sun. “Normally filmmakers have to put this scrim—a diffusing filter—between the light source and their subject,” Peterson explains. “But with the overcast we have here, there’s always a nice soft light—like a natural scrim on everything. If you’re shooting a person, it’s like having a couple of big silks between them and the light. That’s why,” he says with a laugh, “we have the most beautiful rhododendrons and women’s cheeks in the world.”

Because of Seattle’s northern latitude, photographers find the light here ideal, summer and winter, whether a given day is cloudy or clear. “Even at high noon in the summer, the sun is at an angle, so if you want to shoot something backlit, you can manage it easily. You can photograph year-round here and get light at nice low angles.” And generally the isotropic nature of Northwest light renders an object backlit from whatever angle you study it—a circumstance that accounts, says Peterson, for the compelling glow of Northwest grass on overcast days, “It has that kind of fluorescent look because it’s backlit.”

Local artcritic Matthew Kangas feels that colors in general “seem lighter in a way here. Seattle daylight helps us to see colors more clearly.” Kangas is so taken with the beauty of color and light here, in fact, that he has devoted much of his critical career to trying to dispel the myth that Northwesterners are aesthetically fogbound. Some architects“, for instance, avoid reds, feeling the light turns them muddy. Kangas dismisses the vaunted Northwest arts tradition, which concentrates on grays, mists, and murk, as an overhyped minor art movement. “The Tobey-Graves-Callahan thing,” he snorts, “is a cliche. Really, they just represent one side of modern art history here.”

More interesting to Kangas, and more under the influence of the true magic of Northwest light, is a group of abstract painters he calls “the late luminists”: Paul Heald, Joseph Goldberg, Ambrose Patterson, William Ivey, and Max Benjamin. “For these modernist painters,” he explains, “the light here was kind of a latent subject matter. They’re colorists—they explode the stereotyping regional myth of rainy skies as art. There’s a whole tradition here of abstracted landscapes or abstracted interiors with the presence of light coming into the room. Someone like Paul Heald is actually capturing the changing quality of the light here. They’re showing how light and color interact differently in ways that reinforce one another.”

Kangas regards Patterson as the seminal painter in this less-well-known Northwest tradition. “This whole light thing took off when Ambrose Patterson moved here. You look at his Portage Bay, 1954 [a rendition of a Seattle scene on a day when the sun was out during a rainstorm] and you can see the kind of beauty you encounter here. Nowhere,” Kangas concludes enthusiastically, “can you see color the way you can here when it’s raining and the sun is shining at the same time.”

Although “the impact of this natural daylight thing as a subject isn’t obtaining now,” Kangas feels that the Northwest luminist tradition lives on in the work of some contemporary painters. One of them—Gertrude Pacific, whom Kangas describes as being “from the realist wing” of the tradition—made Northwest light an overt rather than latent subject of a series of paintings done in 1976 and 1977. Called the Oyster Light series, the paintings depict Seattle scenes awash in an eerie, evocative light, which imparts a certain disquietude to the scenes it colors. Hypnotic, moving paintings, Oyster Light both captures the essence of Northwest light and testifies to its hold over the receptive heart and mind.

“The term ‘oyster light,’ ” says Pacific, who now lives in Venice, California, “means the color of the light in Seattle. Especially at that hour just before sunset. It’s that time when there’s some kind of wonderful inversion of light. It’s as if everything is suddenly lit in a different way. The sun goes down behind the Olympics, but we still have a lot of light—as if the sunlight is directed upward. It’s pearlescent. The sky reminds me of the inside of an oyster shell. And in my series, I tried to paint that light, which I think is special to Seattle. Even in Vancouver, for instance, the light is much more crisp.”

Pacific describes the light itself as “very much pastel—but not chalky pastel. It’s translucent pastel. It’s not hard and thick—you can see through it. It feels like it has veils over it. It’s not stubborn, it’s not a tough pastel—it’s more eloquent and forgiving.” She first noticed and was moved by it when she was living in downtown Seattle. “Downtown,” she says, “light was one of the only moving, ‘living’ things you saw—it was one of the few things that lived and moved and changed. I kept seeing these subtle changes—from off-white to gray to pearly-white to lavender-white—and I decided to try to capture them.”

Looking at the Oyster Light paintings, you realize that his not only the sky and the material world around us that change color, but the air itself as well. Each of the ten paintings in the series depicts a different spot on the Seattle light spectrum. In Crow Bear Park, a view looking north through Freeway Park, the sky—a hard, dull, vaguely luminous white at the horizon—grades almost imperceptibly toward lavender as you look upward. There is a lavender/gray cast to the air as well, rendering buildings blue-gray, blurring their edges, and softening the shadows cast by them and by the concrete blocks in the park. The air in Avenue Triangle, a view looking south on a clear day from where Denny passes under the Monorail, has a ghostly greenishness—imparting a green tint to the concrete rails overhead—with a dull orange glow on the horizon swelling through white-blue to a deeper, softer blue above. In Buena Vista, you look south from a downtown rooftop on Third Avenue through faded lavender air at an array of subdued buildings whose surfaces in the light look far more alive, the painting suggests, than whoever or whatever may be inside them. Snow Owl/Parking Meter—possibly the best-known of the series—shows the paradoxical quality of Northwest light: as you look east, uphill, along Marion street, you see how in the soft, dull, grayish air the colors on downtown buildings and parked cars take on a depth and fullness that would fade flat under the overpowering light of an unfiltered sun.

In each of the paintings—whether in a clump of crabgrass growing out of cracked concrete, or in light evergreens, or in the riot of foliage in Avenue Triangle, Pacific has captured the peculiar glow of the Northwest’s backlit, reflecting greens. And the more you look at the paintings, the more you see that the subtle color of the air is due to its moisture’s capacity for reciprocal, omnidirectional reflection. Not only does light bounce every which way off aerosols, but it bounces strongly enough off material objects to impart something of their color to the air above and around them.

There is a metaphysical air about these paintings that recalls another line from Thomas Hardy’s description of Edgon Heath near evening: “The place became full of a watchful intentness now.” Pacific’s greatest achievement in this series lies in her having conveyed a certain understated romanticism and mystery that is most characteristic of Northwest light. There is something in its lushness and subtlety that hints delicately, broodingly, at cosmic portent. “It is a light of expectancy,” says Pacific. “You’re kind of unsure about what’s going to happen. It is also a light of possibility, of the recognition of nature, and of enlightenment.”

Something in that quality of the light led her to put animals, rather than people, in the paintings. A bear sits in Freeway Park; a snow owl is perched on a downtown parking meter; an eagle sits atop a lightpole; a doe, standing on a rooftop, looks up, surprised, at the viewer of the painting. “The animals represent the spirits from Chief Seattle’s speech, where he says the ghosts of the Indians will be watching the white man in years to come,” Pacific explains. They are palpable representations of the impalpable yet undeniable pull that Northwest light can exert on the imagination. In this respect, the light around us is as alive and as suggestive as it is dim.

Northwest light’s essential paradox—that its dimness brings to objects a power and depth that bright light takes away—is nowhere more evident than in the flourishing of glass artists in this comer of the country. It is hard to imagine a medium more light-reactive than glass, yet nowhere else has it attained-the artistic heights it has attained in our light-deprived environment. Every summer, artists come from around the world to the murky Northwest to work with glass at the Pilchuck School, and Seattle-area artists predominate in glass collections around the nation. Of the six stained-glass artists collected in the fabled Corning Glass Museum, three are from Seattle. And while the National Endowment for the Arts awarded 17 grants this year to glass artists—only seven of which went to artists working west of the Mississippi—five of them were awarded to Seattle-area glassworkers, a total unequaled by any other city.

One of the five went to Seattle stained-glass artist Dick Weiss, who is also included in the Corning Collection. A Northwest native, born and raised in Everett, Weiss himself seems mystified by his ability to work with light and color in such an apparently colorless setting. On the one hand, he cultivates the quintessential Northwestern resignation to dim light: “We’re like the guy who beats his head against a brick wall because it feels so good when he stops,” he says, laughing. “The gray is wonderful here because it’s followed by sunlight.” Yet rather than try to work with grays and whites in the manner of the modem German window-makers, he gravitates to extremely bright colors and combinations. “For some reason, I’ve always tended to like bright, hard-hitting color. You get more punch-per-inch, you might say, with brighter colors. They’re more aggressive.”

While his instincts seem on the surface to be at odds with his tradition and environment, Weiss feels that his esteem for bright color is the truer Northwest tradition. “The most obvious, simple thinking would say, ‘You live in a gray environment, you’re going to do gray stuff. Everything’s gotta be soft, real pastelly, like it’s coming out of a fog.’ Well, if you look at a lot of the better painters around here right now, most of them do not paint like that. You’re always up against that Northwest School stereotype—but it just doesn’t seem to hold.”

The Northwest’s changing, elusive light has fostered Weiss’ creativity in the way that necessity is the mother of invention. “To expect working conditions to be optimal is like expecting a perfect marriage. With stained glass just the fact that half the day is dark is a killer. You’re depending on light coming through those windows, and half the time it’s dead. And then of course with the overcast vs. the

sunny, you just learn to love the variety. You see that a dull light will pick out certain things—it’s like a sunrise being different from a sunset. The colors at sunrise will be different from the colors at sunset, and the way the light comes in is different, too.”

Part of learning to love the variety, Weiss reasons, comes from working with an art form that changes constantly even in relatively monotonous light like that in Southern California. “The window has to live through a 24-hour cycle, so it changes totally: bright light, dull light, overcast, summer light, light coming in at an angle in the morning, in the evening—it just totally changes all the time. Designing a stained-glass window is like trying to stand on a column of smoke. The damned thing shifts continually. It’s never the same. So I just go with what I get from moment to moment. And I don’t sweat it, because the window changes so much all the time that I just do the best I can standing on that column of smoke.”

One thing Weiss has come to appreciate about Northwest light is that even on the darkest days it is extremely powerful—more powerful even than the lights in his studio. “Even a dull, overcast day like this [it’ is December 22, raining hard, and dim enough at 2 in the afternoon to necessitate driving with headlights turned on] has an incredible amount of candle-power. This is much stronger than fluorescent or interior light. If I put a window up in this light, even with every light on in the house, the gray light coming in is still a lot stronger. So the exterior windows do well even on a very, very bad day. The sun’s just got more candle-power, even coming through the clouds, than interior light does.”

Weiss’ studio is a low-ceilinged, dark, cave-like, and cramped daylight basement with one wall, facing south and made entirely of glass, looking out over the Fremont district. He is putting stained-glass windows up against the glass wall now, showing how they come alive in the natural light. And there is something spectacular in the way each window is dramatically brighter than the outdoor light that illuminates it. His windows seem to extract what little light there is in the air and concentrate it so powerfully that the colors in the glass seem themselves to be light sources

The effect is particularly lovely in painted-glass window with two forms Weiss calls “bleeding trees.” Reddish-orange, 14-branched, cruciform shapes, each in a field of white which is itself surrounded by black, the trees, when put in the light, glow with impossible power. On this dim, smeary day, they shine more brightly, and with far more beauty than the sun in a cloudless summer sky. The eye feasts on them, revels in them, and luxuriates in them with an almost religious fervor. The way they transcend and offer redemption from the dimness behind them is a form of tribute to the lightlessness that mysteriously feeds them and gives them their power.

The window is a distillation of the magic suspended in the air around us, an expression of awe at the power and mystery of our light. To some future historian of myth and religion, it will furnish proof that 20th century Northwesterners worshiped the sun in the manner of those ancient Greek sects who worshipped the Unknown God. “It was a deity they never directly perceived,” this historian will write, “but they saw proofs of its existence dancing everywhere around them, and they fashioned enchanting artificial suns in homage to it. Their air, however dim, was alive with color and light, perceivable more by the poetic soul than the prosaic eye.”

news@seattleweekly.com