King County Executive Dow Constantine signed an executive order on Oct. 3 making substantial reforms to the county’s inquest process for reviewing incidents involving use of deadly force by police—changes intended to increase accountability and transparency.

The inquest process is a longstanding system in King County to scrutinize deaths that involve police officers from both the Sheriff’s Office and various municipal law-enforcement agencies. The county charter gives the executive broad authority over the process, which typically involved a jury of six to four people sitting in a county courtroom tasked with finding out whether the involved officer feared for their life—one of the legal standards for justifying police deadly force in Washington state. (A District Court judge administered the proceedings while a county prosecutor led the questioning as a neutral facilitator.)

However, critics have argued that the system was one-sided since families of the deceased couldn’t call their own witnesses, submit evidence, or even address the jury. According to The Seattle Times, only one local police officer has been criminally charged following a county inquest—in 1971.

In response, at the beginning of this year, Constantine halted numerous pending inquests involving incidents in which police fatally shot individuals—including Tommy Le, the Burien teenager who was shot and killed by a King County Sheriff’s Deputy last summer—to convene a six-member committee of stakeholders to review possible reforms to the inquest process and make recommendations. Those recommendations were released in March.

The most consequential of Constantine’s changes are a new rule allowing involved parties to call upon witnesses and a mandate that inquest juries now be tasked with determining whether officers involved in deaths were following law-enforcement department policy and training. At a Oct. 3 press conference, Constantine said that the goal of this mandate is to help identify law-enforcement policies that are leading to fatal incidents. “If police did not follow their training and departmental policies, we need to know why or why not so that those departments can examine the work they’re doing and make changes in the future that will prevent future tragedies,” he said. “If police did follow training and protocol, we need to determine if there are improvements to be made.”

“The point is not to put an individual officer on trial. It is to make sure that we are asking the right questions and taking appropriate actions,” he added. “I believe the new executive order will provide families, law-enforcement officers, and community members with greater transparency and accountability.”

Constantine’s other changes include finding retired judges to serve as administrators of inquests instead of District Court judges and removing the authority of the King County Prosecuting Attorney’s Office to compel officers to testify before the jury (instead, a senior law-enforcement officer of the relevant agency will be allowed to testify about their department’s use-of-force policy and training). Additionally, families will be appointed an attorney from the county Department of Public Defense to represent them during the inquest proceedings.

Under the new system, juries won’t come away with any binding verdict beyond their assessment of whether or not a given officer followed procedure in a fatal incident. They will only present their findings to the involved law enforcement agency for further consideration.

Currently, nine inquests—including inquiries into the death of Tommy Le and Charleena Lyles, a 30-year-old African American mother who was shot and killed by Seattle police officers last year—are pending due to the hold Constantine placed on them back in January during the reform of the process. Those will be restarted early next year, Constantine said at the Oct. 3 press conference.

The reaction to the changes has been largely positive. Director of the King County Office of Law Enforcement Oversight Deborah Jacobs praised the reforms: “Executive Constantine’s changes to the inquest process address some of the deficiencies that have left the public dissatisfied,” she wrote in a statement. “These changes have the potential to fill gaps in the public’s desire for information, for appointed representation for the families of people killed by police, and for assessment of whether training and policy were followed.”

Meanwhile, the Seattle Community Police Commission released a statement calling the executive order a “big step forward for police reform in our region.”

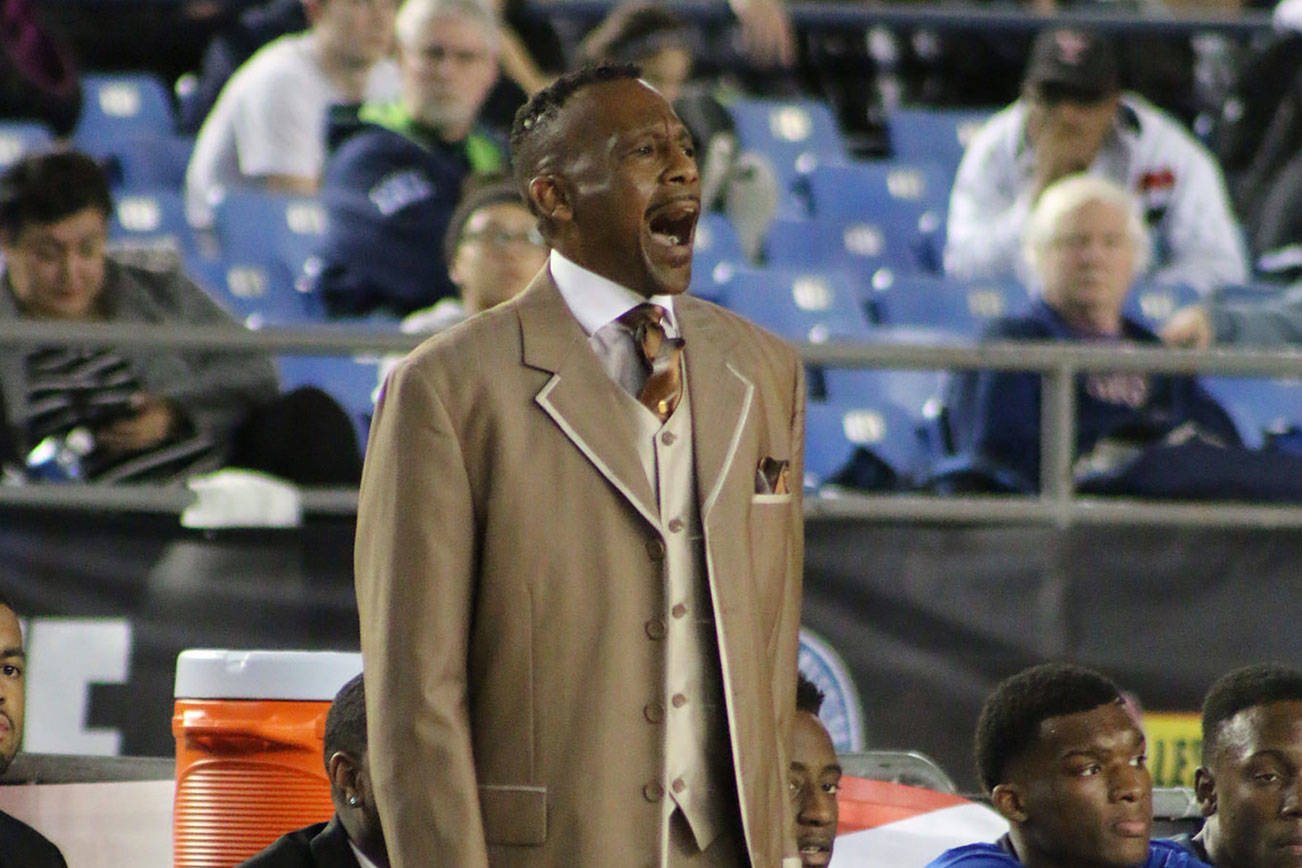

At the Oct. 3 press conference, DeVitta Briscol, the brother of Che Taylor—an African American man fatally shot by Seattle police officers back in 2016—and a member of Not This Time, a local organization seeking to reduce fatalities caused by police, said that the new process will “provide a more satisfactory experience for families and the broader community.”

On the law-enforcement side, James Schrimpsher, a member of the Washington Fraternal Order of Police, stood by Executive Constantine at the Oct. 3 presser and called the reforms a good example of law enforcement and other stakeholders working collaboratively. However, a Facebook post issued by the Seattle Police Officers Guild several hours after Constantine announced his reforms criticized the changes: “Another example of politics being inserted into Public Safety to the detriment of our community,” it reads. “Sadly police are not as concerned with being killed in the line of duty as they are now more fearful of being politically persecuted/smeared in the line of duty. Police Officers are heroes that swore an oath to protect the public. We want to just do our job. We are all for accountability but when did it become okay to make us the bad guys?”

In a statement provided to Seattle Weekly, Xuyen Le, the aunt of Tommy Le and a spokesperson for the Le family—which is currently suing King County over Tommy’s death—said that while the family is “pleased” with the changes to the inquest process, they also want to see the King County Sheriff’s Office replace its internal use of the deadly-force investigation process with independent inquiries conducted by a neutral party. “Only then will the communities and constituents of King County be fully satisfied that truth will prevail,” Le wrote.

An internal review of Le’s death conducted by the sheriff’s office found that his death was justified and within department policy—even though he was shot several times in the back and was holding no weapons or objects other than a pen.