A pregnant woman with pink hair walks into Joe Ray’s apartment in Columbia City. Ray has just finished cooking dinner, and as he boxes up just-out-of-the-oven spice-rubbed chicken thighs, French lentils, and a cucumber salad lightly dressed in yogurt and mint for her to take home, the two chat as if they are chummy. But they’ve actually never met.

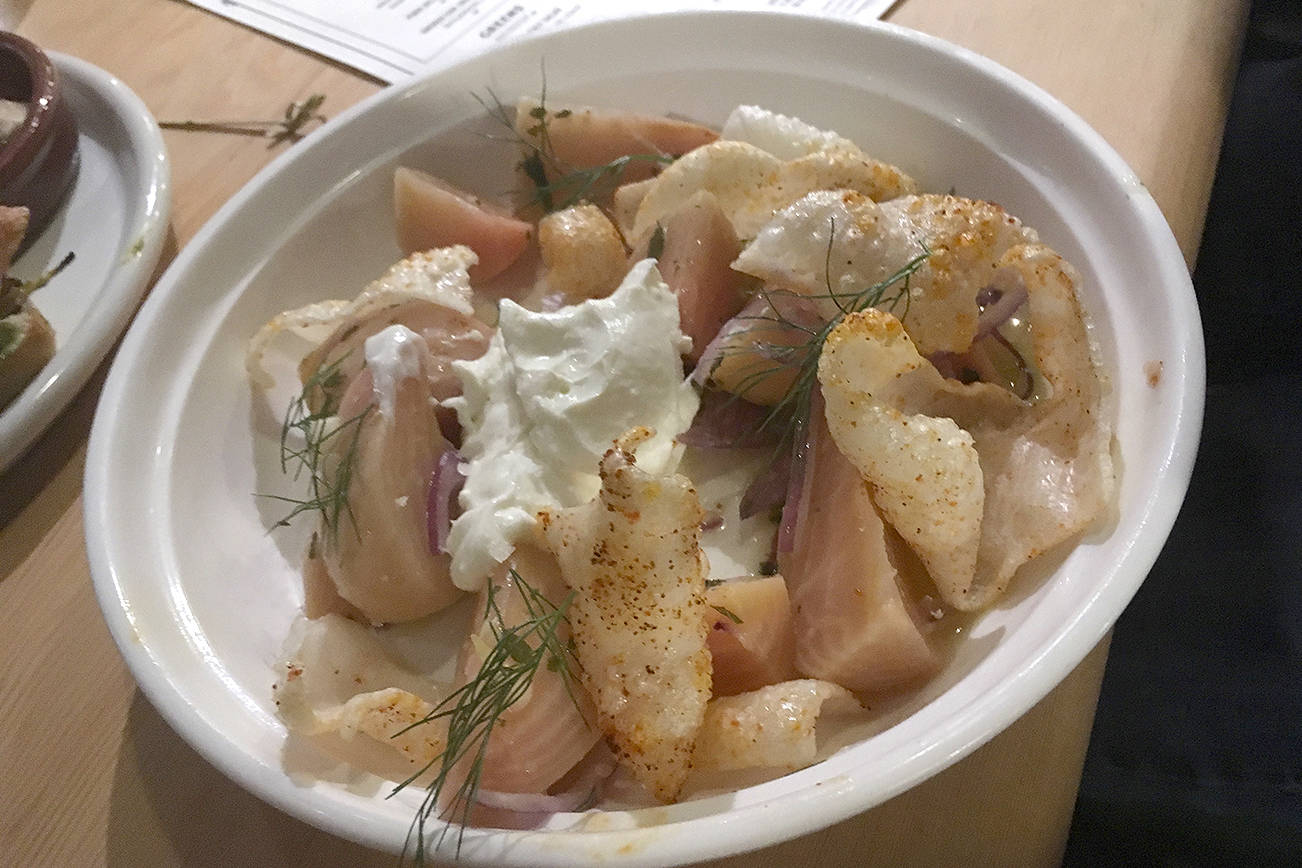

Rather, Ray is a cook for Josephine, a California-based company that set up shop in Seattle just a few months ago. The service matches home cooks with people in their community looking for a delicious meal that’s cheaper than a restaurant. Diners simply go to the Josephine website and search under their ZIP code, and up pops a variety of meals available that evening. If they like what they see—there’s a description of the meal, photos, and a bio of the cook, including ratings and comments from people who have tried their food—they simply place an order and pick it up during a window chosen by the cook on that same night.

Currently, just over two dozen cooks are participating, including Ray. Simone Stolzoff, head of operations for Josephine, says that 95 percent of the cooks on the platform are women, 40 percent are immigrants, and 35 percent are people of color—everyone from the casual home cook to the professional caterer. Most, he says, are looking for a way to boost income, preparing home-cooked meals as a second job, much as many Uber drivers do it to supplement income. “It’s a lot of stay-at-home parents and immigrants looking to generate income, whether incremental or as the primary source for their families,” he says, “but who also love to cook and facilitate community.” In fact, he says that the platform’s most popular cooks are those cooking ethnic food that is reflective of their culture—those who have knowledge of a place and its cuisine.

The audience is primarily parents who want to feed their kids home-cooked meals but are pressed for time, as well as older people who want to connect with their community. Community, in fact, is the backbone of the whole enterprise: the idea that you can buy a meal from a neighbor and bump into or meet other neighbors in the process. It’s far more personal than, say, grabbing carry-out, because you’re actually entering someone’s home and meeting the cook. “You’re not really buying food from strangers because you have common ground via a geographical base and a shared interest in community,” explains Stolzoff. And by meeting the people who cook your dinner, Josephine hopes to facilitate transparency in the whole food-supply chain. “When you meet the cook, there’s naturally more knowledge and transparency. And cooks who use Josephine are buying local and supporting local economies.”

But is the food safe? Yes, says Stolzoff. As part of the rigorous onboarding, Josephine thoroughly inspects all its cooks’ homes and requires each to get a food-handler permit. Staffers with master’s degrees in public health ensure that safety standards are met, while others taste-test to see if the food is up to snuff and if the home cooks are capable of cooking in bulk. Ray, who has cooked professionally in restaurants, says that one of the hardest parts is not knowing how many people you’re cooking for until the day of, yet he suspects that will become less of a problem as he builds a base of loyal customers. He’s already had repeat diners, including one neighbor who took a seat on his sofa while he boxed her food. Though the cook’s home is not meant to become a hangout, Ray says he doesn’t mind when regulars chill out for a moment or two as they wait. That’s the kind of casual, inviting atmosphere Josephine is promoting.

Aside from providing home cooks a place to sell their food, Stolzoff says they really want the cooks to think of themselves as owning a small business, and they are trying to empower those who might not have the business experience by offering classes and tools, like spreadsheets, to help them learn to scale and to market themselves. “A lot of them have not worked in the food industry or have been disenfranchised by the food industry,“ he says. “We want to lower that barrier.” To that end, Josephine has teamed with local partners such as Seattle Tilth and the Center for Inclusive Entrepreneurship, which helps refugees learn to cook as a way to enter the world of commerce.

But why did Josephine choose Seattle as its second market? Demand, but also because of our foodie and entrepreneurial spirit and a population open to innovation and new models. After all, Stolzoff adds, “There’s no precedent for consumer behavior of going over to a neighbor’s to pick up dinner.”

food@seattleweekly.com