Nothing at the 2015 Seattle Art Fair inspired such universal awe and chagrin as the Forum Gallery booth, which devoted its large space exclusively to the artwork of Al Farrow. Now Seattle audiences can have the intimate, quiet experience that his sculptures deserve at Divine Ammunition at Bellevue Arts Museum, his first major retrospective in the region.

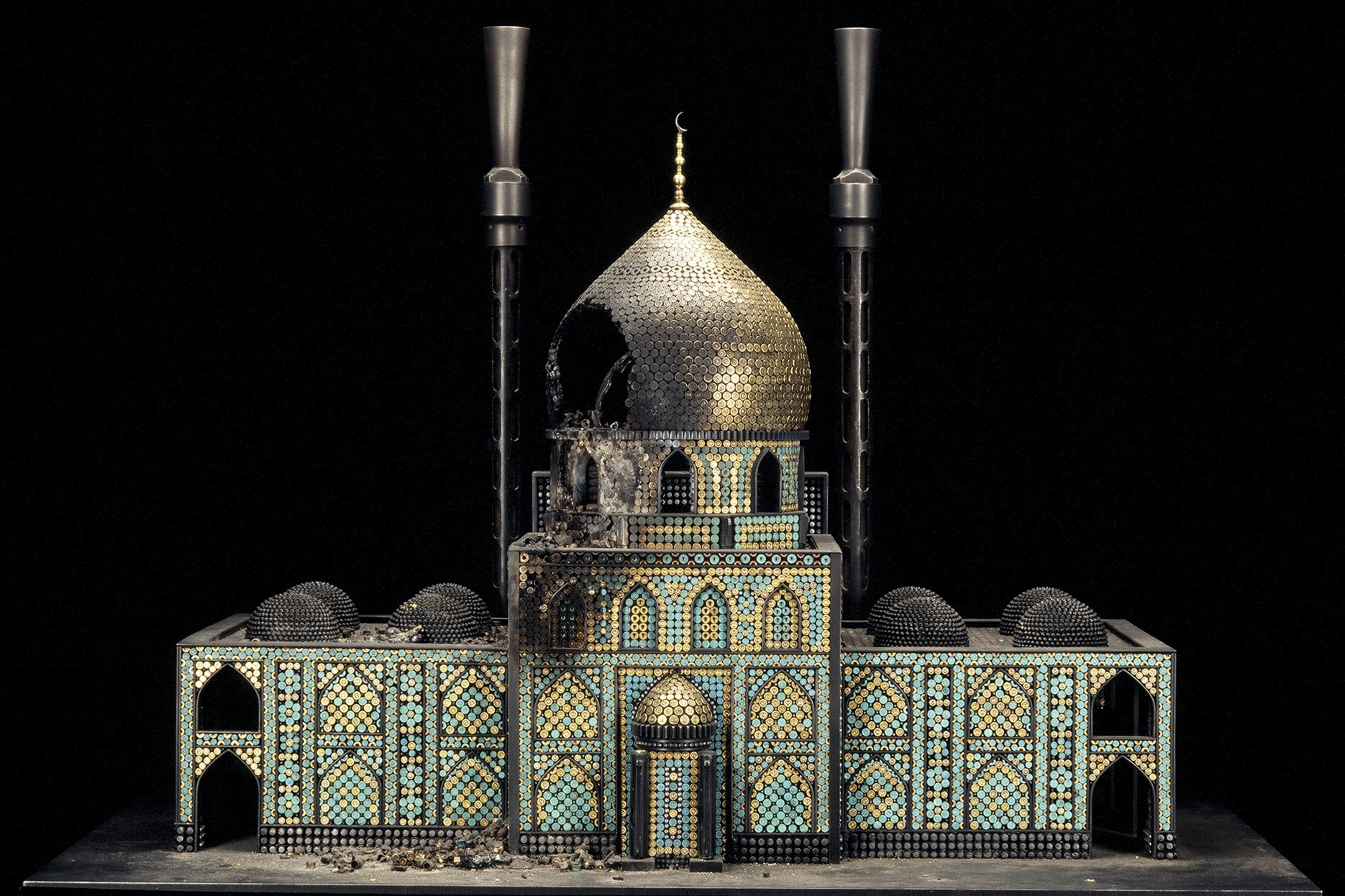

At a distance, one can see that Farrow’s sculptures of mosques, synagogues, and cathedrals are well-wrought and ornate, so one moves in for a closer look. Drawing near, his faithfulness to the rich adornments of Abrahamic sacred architecture becomes more apparent—but something is off. You put your nose to it, and it hits you: Everything is made of guns and munitions.

The flying buttresses around a gothic cathedral are pistols. The colorful “tiles” that cover the inset walls of a mosque are bullet casings. The columns of a medieval mausoleum are mortar shells. Peering through the windows of a synagogue to see a Torah swaddled in its velvet mantle, you may not even notice that the exterior is made of thousands of balls of shot, welded into pebbly walls.

Nothing in Farrow’s work simplistically equates religion with violence, but it draws a connection. One easily makes that connection to start, but ought to pursue others throughout Divine Ammunition. The military-industrial complex that created many of these weapons is pervasive, but it almost disappears through Farrow’s virtuosic adaptation of its products into building materials. Even less visible are the dogmatic political and economic forces that drive war for profit, existing in tandem with religion.

Only an especially partisan mind could see Farrow’s complex artworks and reduce their content to a talking point, or dismiss them out of hand as merely disrespectful. Unfortunately, in this time of information saturation, this sort of gross oversimplification is practically treated as a survival tactic of its own. Divine Ammunition is a strange refuge from all of that, given that it surrounds one with countless instruments of death, but a refuge it is.

It is also genuinely reverent. It recognizes that these sacred spaces serve as refuges, too, and historically have been the cradle of great art and philosophy. This has not protected them from becoming targets of violence in their own right—far from it. For instance, Bombed Mosque is a testament to the transcendent beauty of Islamic architecture, so much of which has been scarred by war. Its gorgeous dome is blasted open on one side, and its debris has rained down into the chamber below, which is just as intricately wrought, though obscured by shadow.

Farrow works from the inside out, cutting no corners. In fact, Bombed Mosque was created as a whole piece, which he then attacked with a welding torch. To test whether this technique would work, he first created and destroyed another dome of the same size. The bullet casings he used as building material were patinated by Farrow himself using chemical baths to achieve a range of colors. Every aspect is measured and drawn from authentic sources. Some works are faithful, to-scale homages to real structures; others are merely inspired by the architecture of particular eras and regions. Each is uniquely breathtaking in its ingenuity and complexity.

“Skull of Santo Guerro,” Courtesy Bellevue Arts Museum

If Farrow were interested in sacrilege, there are a million easier, cheaper, and faster ways to show that. Such crassness is ubiquitous these days, and as it seeks to provoke a very specific reaction, it is more akin to propaganda than art. Farrow seeks to provoke curiosity, questions, and empathy, and that’s why it is important viewing for us today.

At its best, art springs from inquiry and expects additional inquiry from the viewer. At its most insidious, propaganda leads one to a specific conclusion, perhaps without even explicitly stating it. Propaganda discourages or punishes curiosity, while art inspires and rewards it. By being so accustomed to consuming propaganda, we sometimes begin to treat art with the same reactions. Because of its subject matter, Farrow’s work may be especially prone to that treatment, and I hope that as critics and viewers we resist this impulse to apply a singular approach or judgment.

This has always been Farrow’s intent, dating back to the 1960s when he began making work as an extension of war protests. Holding a sign in marches didn’t seem to be all that effective, so he used his metallurgical background in work that would get people questioning and conversing more than a sign ever could.

Four decades later, humans are only more efficient at killing one another. The quagmires of numerous wars in Muslim countries have made it increasingly difficult to separate capital from religion from virulent extremism from race. If at Divine Ammunition one is hoping for easy pronouncements to quiet these concerns, one will be disappointed.

But while wrestling with the more nuanced questions that may arise as one ponders a reliquary to Farrow’s invented Santo Guerro (for instance, an enshrined skeletal trigger finger or a whole femur), one doesn’t drift entirely into the abstract. The implied threat and brute, beautiful physicality of Farrow’s work grounds one’s experience in the real world and inspires real empathy, however melancholy.

The ravaged sculpture Burned Church is made of almost unrecognizable rifle barrels excavated at Verdun. These weapons were buried in bloody mud alongside the men who carried them into battle and never returned. In another room, three life-size doors depict entrances to a mosque, a synagogue, and an American chapel. Each is defaced by vandalism or bullets. The mosque door is, naturally, the most decorative. Its knockers are attached to domes with fluted surfaces—two halves of a so-called “guava” bomb. Those flutes cause the sphere to spin and spew hundreds of steel fragments over personnel on the ground when dropped from planes. How strangely beautiful they are when reduced to mere adornments. How much human potential and ingenuity is spent on the creation of things to kill and maim? Is there redemption in removing their deadly uses and making them merely sculptural? Is there any redemption at all?

It seems that in spite of all the transcendent ideals in human philosophies, our epoch (and especially America) seems most convinced that redemption comes only through suffering. This notion underlies our punitive justice system, our haste to make war, our complacency about violence within our own borders. It is worth noting that despite his constant stockpiling of guns and materials for his sculptures, Farrow has never been questioned by authorities. In fact, he generally keeps his artwork a secret from dealers, who might otherwise not sell to him. Their reverence for guns is supreme, and they would not have him destroy or “waste” them, as he once overheard a man say of a gun in one of his sculptures. Farrow may have invented Santo Guerro, but the cult of the gun preceded him and counts many among its faithful.

No matter what one’s position may be on gun policy, again, one must not boil these works down to a singular judgment or issue. One should observe, think, allow for empathy to build, and if one is so inclined—in seeing the evidence mount that the deathly inspiration for Farrow’s artwork is itself immortal—say a prayer. Divine Ammunition, Bellevue Arts Museum, 510 Bellevue Way N.E., bellevuearts.org. $12. Ends Sun., May 7. visualarts@seattleweekly.com